Sorry about that intrusion of theopolitics, and especially on a Thursday. I've decided to try to adhere to a schedule with these things. If I write anything at all, I'll try to do particular topoi on particular dagum:

Monday: Things to do in general.

Tuesday: Regrets for things done.

Wednesday: No idea.

Thursday: No idea there, either.

Friday: Recherche du temps.

Saturday: Theopolitics (the sabbath, after all).

Sunday: Religion.

I'm going to follow that schedule, starting today, by talking about music.

"Music might tame and civilize wild beasts, but 'tis evident it never could tame or civilize musicians." -- John Gay, PollyI mentioned the other day getting a new amplifier. It hasn't arrived yet, and everything in this town is closed on Sunday anyway, except for the restaurants, and no one cares if the underclass has to work on Sunday. I was at Amazon.com the other day, and it said,

"Dear The, we have the following recommendations for you in Music."

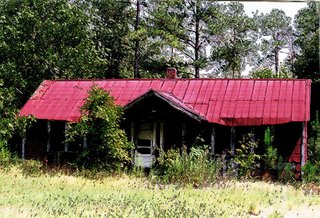

They call me "The," which, of course, is a level of intimacy that I allow only to my closest friends. They recommended Our Endless Number Days, by Iron & Wine. That "band" is just one guy, for the most part -- a guy named Sam Beam. He lives in northern Florida, which is a desolation very like southern Georgia, eastern Alabama, and western North Carolina (and all of South Carolina), so I figured I'd hear the record, especially since he had a song called "Sodom South Georgia." I couldn't imagine any town in that area earning such an epithet.

Now, the South is where all the music is made, but it's not where any is heard. I had to rely on Amazon because I'm in a town with a single radio station and no city near enough to get other stations. It's the sort of place that makes XM and Sirius prosper and makes dullards happy. You have a choice: hear nothing or pay money to hear something. There are no record stores in town except for that evil Megalith -- the one that had even the dumb old Eagles change their record's title from "Hell Freezes Over Tour" to "Farewell Tour," because H-E-double hockey sticks is a curse word. The paradox that the soil generates music with its weeds and peanuts and yet maintains a silence around the people is not that surprising. After all, American music began with greater isolation.

When you get to hear nothing meaningful or interesting, you have the choice of either becoming a monotony junkie or a freak. If the former, you will prosper. If the latter, you will get stoned, stumble about, and either die young at home or go on tour and die young. The advantage to learning to love monotony is huge, and yet, given all the penalties involved in it, a good number of folks would rather die, would rather lose acceptance and friends. God bless them. God have mercy upon them. Normality and homogeneity are thick pap. The more you swallow, the more comfortably you swallow. The more you consume of it, the fatter you get and the less thinner and rarer foods will satisfy, the more alarmed you will be when a spice accidentally falls on your plate.

The freaks will be the smallest of minorities, and they will mistakenly think that they must rebel against each other, as well as everyone else, and their adolescent hormone intoxication will get them to misattribute dullness to malice. They are no threat, really. They cannot influence others very powerfully, and they give a safety valve and sublimation pathway to everyone else, so there is nothing to worry about. Instead of starting a union, they'll write "The Ballad of Curtis Loew." Even if they rant "The Southern Thing," they're just getting the choir to pump its tattooed fists. No, no. No harm, no foul.

I'm not suggesting that freaks are more useful in other regions of the nation. They're not. I'm not suggesting that the rest of the nation isn't lumpen. It is. I'm not suggesting that thinking is an occupation for any part of the nation, nor that assumptions are regularly questioned anywhere. No, such things would be unAmerican, if not just unnatural. It's just that there is this thing Kevin Phillips is supposed to have devised called "The Southern Strategy."

"How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?" --Samuel Johnson, Taxation No Tyranny (1775, an answer to the protests of the New England colonies).

I don't intend, at this point, to debate from Johnson's narrow point of view, but his broader point of view, that liberty begins at home, is still acute. Instead, I want to answer him. I want, two hundred years late, to tell him why he hears the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of negroes. It is because of isolation. It is because of the efficient marginalizing of difference.

The South is not Atlanta, Birmingham, Gainesville, Tallahassee, Columbia, Charlotte, or Richmond. It is the area between. The South is the interstices between cities. The south is the monocultures that organize themselves around small loci, nearer to the definition of "network" in Johnson's Dictionary than anything offered by Rand MacNally. These local knots are excellent at sending its discontents out along a filament away. The strands are made up of the dissident voices, the gifted and drunken who cannot be contained, and the knots are the power, the small clusters of voices and minds in accord and accomodation, with books of ettiquette in their heads and elaborate rules for dealing with acceptable and unacceptable difference.

I mean in no way to say that it is a bad thing. It is simply a thing that naturally occurs when communities are small enough to establish equilibrium.

So, in such isolation, the voices of concord grow to a point of coercion, and they can easily discount any fact or fiction that would threaten the unison. We yell for liberty because we want more liberty from the things that are not us, not ours, not subordinated to our rules. If your rules are taxation, then we want out -- we do not see you, and you do not honor us, and you do not operate by our rules, and you try to tell us that some of our rules are barbaric. Therefore we need to be free, for freedom is isolation.

The Southern Strategy hinges upon this desire to be separate, to be isolated, to pay no tax to those we cannot place in our order, to obey no law passed by those whose faces we do not know, to pay the salary of no legislator whose family is unknown to us. It is dependent wholly upon those cut off from the upset and unregulated freedom of the cities wishing to desire, most of all, to be entrenched, moated, to be in entire solitude, to be able to cast out its jarring singers and hear no words of the frightening song.

No comments:

Post a Comment