"No one undergoes a stronger struggle than the man who tries to subdue himself." -- Thomas à Kempis, Imitation of Christ 3, iii

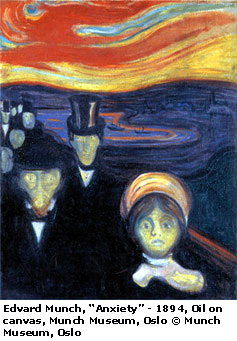

Shame is the theme for some authors, and yet it is a feeling that is at once elementary and advanced. There is the basic form, which is actually regret mixed with fear, and then there is an advanced form, which takes that as its based and tunes its song with added notes of memory, inevitability/doom, and awareness. The last one is so refined and piquant a feeling that it can, in its wake, leave us with a shattering sense that all awareness is shame, that any further awareness would result in further shame. I suspect that James Joyce, at least in his Dubliners phase, had this conviction, and a good many of us who read him have to agree.

I recall the first... no, I won't speak of that, as it was not what any of you would expect and is not actually embarrassing at all... sense of reflexive shame, the shame that requires apology to no one, came when I was in the library. I cannot recall now whether it was elementary or high school, but to me there is not much difference in the two, as only the earliest years of the combined experience were tolerable. The girls were outside the glass of the cube where the tables were, and I was inside the study terrarium with a couple of friends. I say "the girls," because they were interchangeable in my mind at that time. They were the Bub Club. Since I had no sisters and was fed a daily diet of pejoration by my older brother, I was even more unequipped to handle what came next with poise.

They giggled. They giggled at me. It had to mean something. I canvassed all my female friends, demanding that they explain the coded signals of the giggle. Boys would be purposeful in such a thing. It would mean sex or violence, which were the only two possibilities in boy world. Was I being laughed at, or was one of them being laughed at for liking me? Either way, I was there as a body, and I didn't like it.

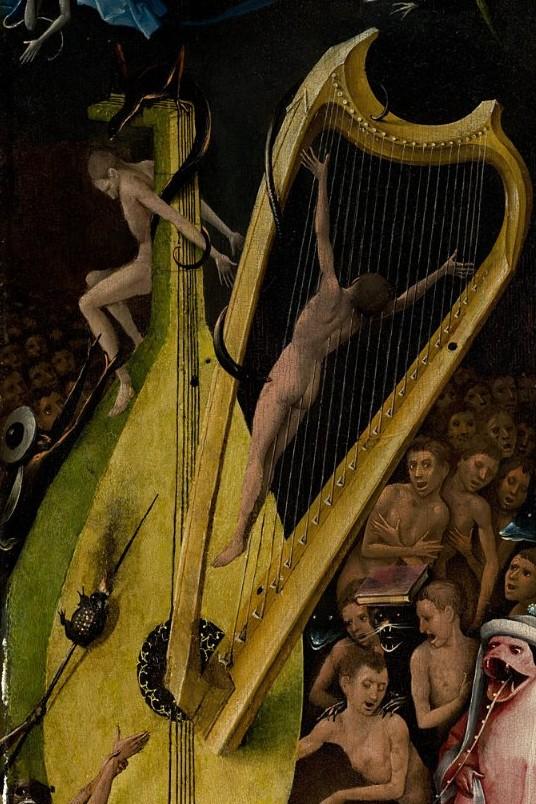

“Can you imagine the pain, the dull imprisoned suffering, hewn into the matter of that dummy which does not know why it must be what it is, why it must remain in that forcibly imposed form which is no more than a parody? Do you understand the power of form, of expression, of pretense, the arbitrary tyranny imposed on a helpless block, and ruling it like its own, tyrannical, despotic soul? You give a head of canvas and oakum an expression of anger and leave it with it, with the convulsion, the tension enclosed once and for all, with a blind fury for which there is no outlet. The crowd laughs at the misery of imprisoned matter, of tortured matter which does not know what it is and why it is, nor where the gesture may lead that has been imposed on it for ever.” – Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles, “Treatise on Tailor's Dummies.”

I had thought little of myself as a being. My brother, for instance, had considered his looks, his demeanor, his musculature, and his goals. I had considered my personality, my misery, my soul, my anger at religion, my impatience with my teachers, my desire to create an alternate science fiction universe where I was in control. Neither my brother nor I had considered our selves. Few people do, after all. It's too time consuming, when we're young, and it's too boring, when we're old.

The full self is not merely body, nor mind, nor soul, nor some layer cake, nor even the batter in the blender of all three, but all three with a knowledge of their heterogeneity and friction. Coming to that is a long, long trek. At the time of the giggles, I had managed soulfulness, and mind was on its way, but at the cost of, as Dave Thomas says, thinking of my body "as a way of getting my head from place to place" (said on a "Tonight Show" appearance many years ago). When the girls giggled, they made me think about the fact that I had flesh, that I was occupying space, that my desires had to be fulfilled through body, that the body, which had always seemed, had always, in fact, been the thing I had no power over, would have to be reckoned with. I was ashamed. I wanted to apologize.

Don't imagine that there was something particular that I needed to apologize for. I was in no way outstanding. I was purely average, in fact. Aside from, at that point, a big chip and an aggressive brain, there was nothing to notice, save for naivete.

Since that very early experience, which I have discovered many young men shared with me, the body has been my particular weak spot. It is not, of course, the only avenue. For me, it remains the dog whistle, because it is what I will soonest forget. Tell me about how my food causes uncountable death, pollution, and unthinkable misery, and I will feel that same sudden awareness, that awareness undesired, that fear mixed with guilt and a need to apologize for no particular act, but for simply being. Tell me how the iPod or apple I purchase involved a million miles of diesel fumes, how Gilbert eating a grape meant transgenic Monsanto killer tomatoes, and I will flush red. Nor, of course, is my sex a help in this. Young girls get the body shame far earlier and never have it let up. (The reason that the body was something always beyond my control was that, although I look like a very healthy animal now, I was a very, very, very sickly runt of the litter when young. I was born with birth defects in my heart that seemed to have a Eugene O'Neill sort of determinism for me. Biorhythms and biofeedback was of limited success, and pyramid power didn't work out.) In fact, the reason that the anecdote I began with is notable is merely that it is novel for boys. For girls, it would be one flea bite amid an amputation.

I have seen, since I have fallen into the modern life of apologizing for being where I am and who I am, that others sometimes do so when the pathway is the mind, but more rarely, and they virtually never do when it is the soul.

“And when the hourglass has run out, the hourglass of temporality, when the noise of secular life has grown silent and its restless or ineffectual activism has come to an end – when everything around you is still, as it is in eternity – then eternity asks you, and every individual in these millions and millions, about only one thing: whether you have lived in despair or not.” – Soren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death

I can leave you to your own scenarios and let my clever reader get ahead of me, if she wishes. However, essentially it comes down to the fact that some people find themselves being forced to become aware of their mental pathways, their mental development and process, when they had managed to avoid thinking about it. When they do, they feel shame. I am not speaking of the, "Shucks, I don't know nothing about no quadrilateral equations" dodge. I mean someone silent at the side of the table, unnoticed by everyone else, suddenly feeling very small, very sad, afraid, and aware. In the United States, it's not so easy to find these situations -- partly because of anti-intellectualism, of course -- mainly because the mind is inside, and the body is outside. It's not easy to see or prove someone's mental process, and therefore it's not likely that the other person will be compelled to be aware, if he doesn't want to be aware. For the soul, the scenarios are non-existent.

What I can say is that I'm sorry. I can further say that I am sorrier still for the fact that, at this point in my life, when the hero of Steppenwolf was about to get out his straight razor, I go back to the most fallacious folly of them all. I envy.

While we who have flashes of involuntary awareness experience complex shame and thereafter feel the need to apologize for ourselves, justify ourselves, make up for ourselves, other people seem impervious. They are in the same situations, but they do not have the shame. We, some time around the age of twenty, decide that they are enviable. "I should have been a mobile home dweller like X," we say, "because then I'd have no idea that I wasn't happy." That's bull, of course, and we'd be terribly miserable, or dead. We are tailor's dummies in our own shape, and were we pressed into another we would spring back into this (Bruno Schulz's father was wrong). The people who feel no shame manage their trick not by being stupid, but by being without a self.

If you do not develop your soul, you cannot feel another's pain. If you do not develop your soul, you cannot engage God as a living being. If you do not develop your soul as part of your self, you can only hate your parts.

So, follow me down this road for a moment, just out of morbid curiosity. I have no answer, but I have a hypothesis. Suppose that a person is active all the time. A situation occurs like mine in the library. The boy in the box in this case hears the giggle and puffs up. He knows he is the center of attention, assumes it's because the girls all love him and struts over. He does not become aware of self, because he is not thinking out. The same person in a meeting who is unable to keep up with the thinking going around him just waits for the answers. There is no awareness involved, because he wants answers, and these people should come up with them. Now a woman finds that her food involves peasants suffering. She thinks that someone should do something about that, probably. It's not her problem. Those people should move, she might think.

The point is not that these are stupid people. They aren't even selfish people, per se. Instead, they are not selves. They are not integrating the components of self to be in touch with the moral, the social, the physical, and the mental. They act. We, on the other hand, inhabit and must therefore be conscious and aware. We are better off, but we live out one very, very long apology.

"It hurt while I got it, and the amount of pain is the amount of deserving to the acquisition" is one of the full statements of "earning" in the United States. Therefore, the woman who can eat all she wants and never lose a curve or gain a lump has not earned her figure, but the woman who frets at the gym and diet counter has, and the man who lifts barbells has earned his muscles more than the man whose body is simply large and hung with muscles.

"It hurt while I got it, and the amount of pain is the amount of deserving to the acquisition" is one of the full statements of "earning" in the United States. Therefore, the woman who can eat all she wants and never lose a curve or gain a lump has not earned her figure, but the woman who frets at the gym and diet counter has, and the man who lifts barbells has earned his muscles more than the man whose body is simply large and hung with muscles.